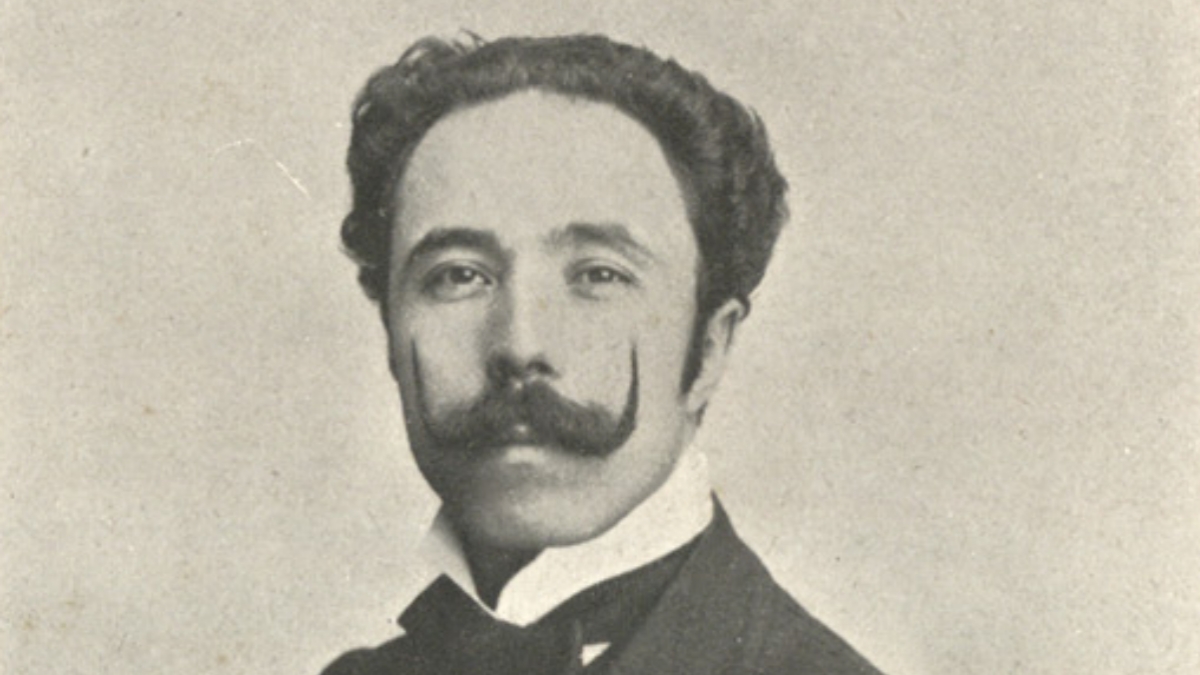

To be a successful and widely revered God, one needs two seemingly opposing characteristics: ethereality and relatability. While we want our Gods to be otherworldly and intangible, we also need the comfort of familiarity. The advent of Christian divinity in India therefore, posed a unique challenge: how to relate to pale Gods that don velvet robes in favour of our home-grown cottons and silks? Angelo da Fonseca, a relatively unknown Goan painter, found a unique and controversial solution to this problem.

Fonseca was born in 1902, the last of 17 children in a family of Catholic landowners. Although his first ambition was to study medicine, he once had an epiphany during his prayers. He realised that he was meant to be an artist and enrolled in the JJ School of Art, Mumbai. But its western academic training did not appeal to him and he moved to Shantiniketan in Kolkata to learn from the great artist and teacher, Abanindranath Tagore (nephew of the poet Rabindranath Tagore). By the time he left, he was determined to bring about a renaissance in Indian Christain art.

An ardent Marian devotee, he painted several pictures of the Virgin Mary donning traditional Goan sari and blouse. The conventional European missionaries in Goa at the time could not tolerate this, and the Portuguese expelled him from their colony.

His creation of the pale-skinned Madonna, clad in a simple blue and white robe with a halo, is a familiar sight in every Goan Catholic household. But most Catholics wouldn’t know it as a Fonseca masterpiece!

After leaving Goa, Fonseca settled in Pune. There he is said to have been influenced by the Spanish Jesuit, Father Henry Heras, a widely respected archeologist and historian who encouraged Indian artists to paint native themes.

Fonseca was a prolific and versatile painter; he carved on wood and slate and worked on scrolls, stained glass, wax drawings, pencil sketches and baked clay. He has over 1,000 works in watercolor, oils, murals, and paintings. Some of his works are in St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai, Missio Museum in Aachen, Germany, De Nobili College in Pune and Rachol Seminary in Goa.

But as Arrowsmith notes with great sorrow, there is this impression of Fonseca among art historians as rather a provincial figure, of interest probably only to practicing Christians. The artist’s intense interactions with other traditions of sacred art in India have thus become obscure, and his most experimental and best work left largely in the dark.

Fonseca died unexpectedly of pneumococcal meningitis at 65, leaving behind his widow, Ivy, and their only daughter, Yessonda. His widow gave his paintings in her possession for an exhibition to the Pilar Fathers, in 2002.

In a sense, Fonseca’s art was an attempt to bring out the humanness and relatability of Gods. He was dismayed by the “machine turned plaster statues, painted like a picture on a chocolate box, which very often, after a fall, become armless and have their head stuck back in place with red sealing wax.”

And so, his imagery used Indian settings, clothes, symbols and references. For instance, his brown-skinned Mother Mary donned a sari, sat on the floor cross-legged and held a lotus instead of a lily (the traditional Christian symbol of purity).

However, this inculturation did not go down well with the Catholic Church. His work was mired in controversy and he was subsequently condemned and expelled from Goa by the Portuguese Colonial Government.

Fonseca’s uniquely cross-cultural oeuvre has received much-needed attention in recent times as it brings up questions of modern Indian identity and its relationship to art, religion and worship.