~ People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI) journalists share ground reports on developmental issues in Maharashtra.

Families evicted to make way for the newly commissioned Samruddhi Mahamarg, also known as the ambitious Mumbai-Nagpur expressway, schools demolished for development projects and villages emptied for hydropower projects in Maharashtra and other stories of displacement took centre stage at the recent MOG Sunday session, PARI: Stories from the Margins at the Museum of Goa, Pilerne.

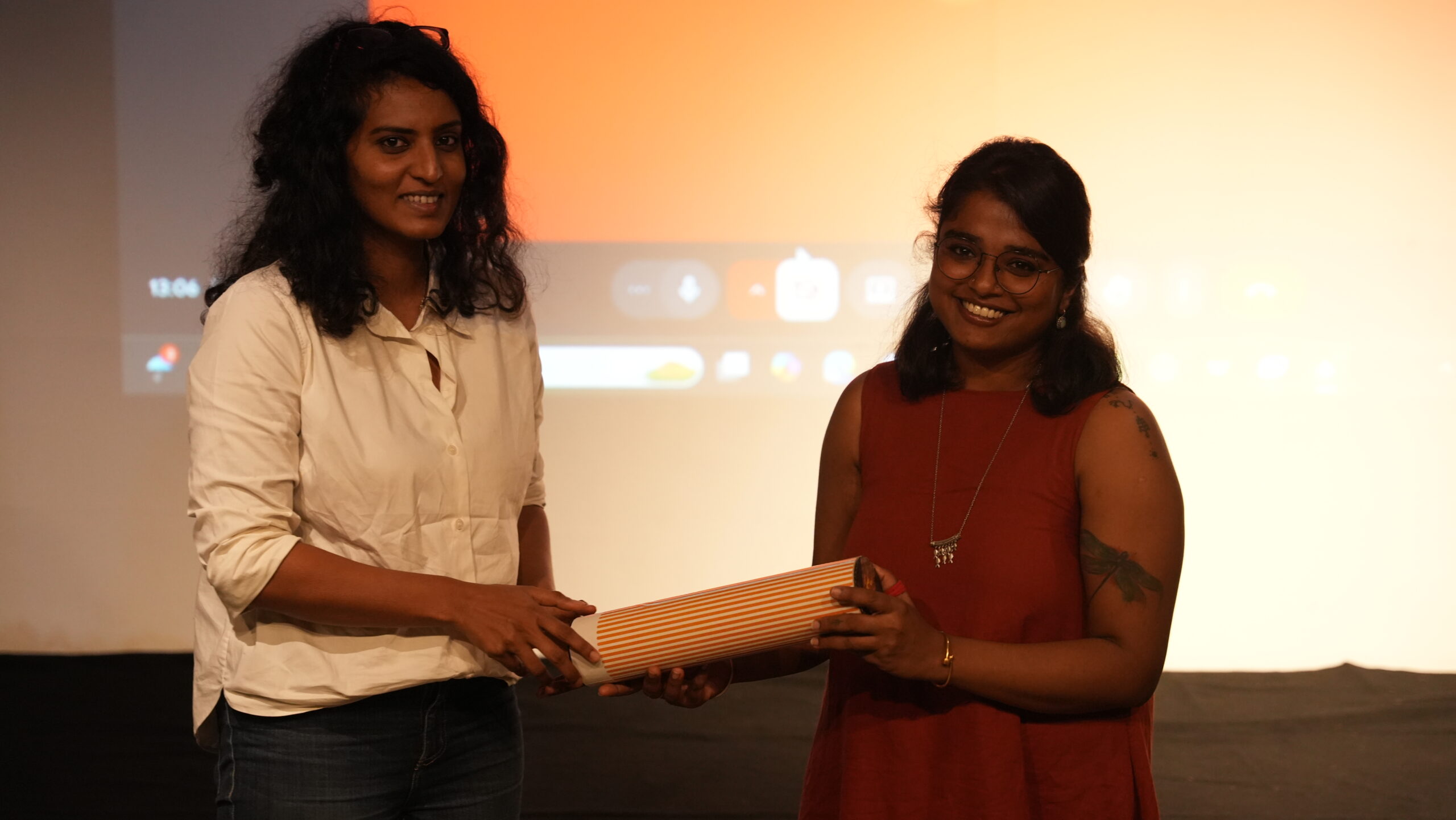

Jyoti YL, a journalist with the People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI), a multimedia digital journalism platform, shared accounts from her ground reporting in Maharashtra’s tribal and rural districts, where everyday survival often means living without basic support from the state. “For people on the ground, it often means displacement, despair and invisibility,” said Jyoti during her virtual talk at MOG Sunday, where she was accompanied in person by her colleague at PARI, video journalist Shreya Katyayini.

Jyoti also spoke about rural communities displaced by large projects, including families dependent on rivers for fishing who were evicted without compensation to make way for the 701 km Samruddhi Mahamarg, one of India’s longest greenfield road projects. She also described how hydropower projects in the Western Ghats uprooted entire villages. “They were just asked to leave the place, even though they had proof of property tax. With the (construction of the) highway, their livelihood from fishing was also gone,” Jyoti recalled.

She also recounted the story of Tulshi Bhagat, a woman who collects palash (Flame of the Forest) leaves in Shahapur and travels over 40 kilometres to Mumbai to sell them in the flower market. Nights on pavements, harassment by police and meagre earnings define her routine. “Do we ever think about who these people are and where they come from? For Tulshi, this daily ritual of gathering leaves and selling them in Dadar is survival,” Jyoti said.

Children too are caught in these cycles, Jyoti said. The sons and daughters of sugarcane and brick kiln workers are often denied regular schooling. Makeshift classes run by local groups are their only option, while state promises of support rarely materialise. In some areas, government schools have been shut or merged, forcing children to walk long distances to attend classes.

Her colleague, video journalist Shreya Katyayini, reflected on how such stories are told from a rural perspective. Building trust with communities, she said, often means spending time with women as they fetch water or share meals before a camera is switched on.

“When I walk into a house, I don’t pull out my camera first. You have to almost become invisible so the story continues to be about them and not about you,” Shreya said.