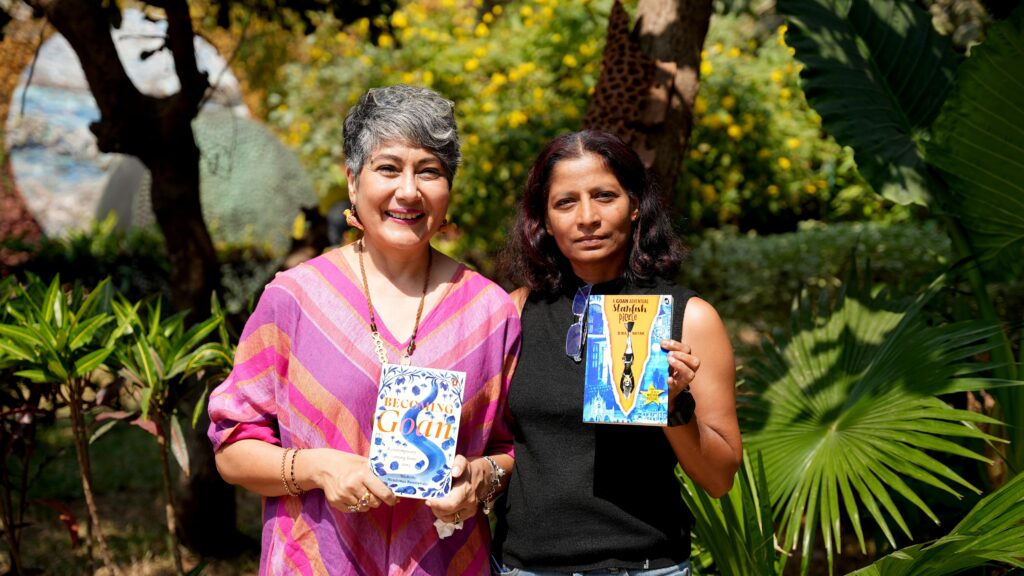

The gap between the traditional practices in the Goa of yore and contemporary Goa needs to be bridged in order to understand what it truly means to be Goan, according to authors of Goan origin Michelle Mendonça Bambawale and Bina Nayak.

At the recent MOG Sundays talk at the Museum of Goa, Pilerne, ‘Goan Identity Through Two Books’, Bambawale and Nayak discussed their books, the fictional ‘Starfish Pickle’ and non-fictional ‘Becoming Goan’, respectively, that highlight the idiosyncrasies and their engagement with the amorphous yet defined ‘real Goan’ identity.

“I have tried to show a side of Goa that people don’t want to see, like how the remains of tourists who drown are collected by divers from the Navy… the flip-side of the partying and drugs, and more of the ‘traditional Hindu Goa’, as most of the writing I have come across deals with the ‘Catholic Goa’,” said Nayak.

Nayak further stated that “The protagonist of ‘Starfish Pickle’, Tara Salgaonkar, is torn between the dichotomy of ‘Goa as a party capital’ versus the ‘religious Goa’. However, I have observed that there are incredible similarities between the trance music culture that forms part of Goa today and the fervour experienced during the traditional zatra (feast)”. Her book has been adapted to a 2023 Bollywood film ‘Starfish’, starring Milind Soman and Khushali Kumar.

According to Nayak, the emergence and sustenance of trance music began because of the religious beliefs prevalent in the coastal state.

“We still believe in animism, the belief that objects, places and creatures possess a unique spiritual essence. Paganism is still practised in the state. When the music scene and full moon parties began, people found support among the tribals and people along the coastal belt, because zatra and zagor (feast) are akin to full-on religiously sanctioned trance parties,” said Nayak.

However, Nayak stated that there is still a section of the Goan population who look down upon trance music culture because they are more ‘cultured’ and have a different belief system.

Bambawale traces her experiences in Goa and notes several ways in which Goa has transformed since the 1970s, rendering much of it unrecognisable, but still carrying pangs of familiarity and nostalgia.

“We would travel by bus from Bombay to Goa as taxis were expensive and still are — so that has not changed! We used to draw water from the well, there was no electricity, no walls or gates around our house, and hardly any restaurants, so we had to walk for ages to find a place to eat out. Now, there are more restaurants, cafes and bars than you can imagine, but their ubiquitousness comes with the cost of no parking space. There is also so much construction, substandard sewage systems and water shortage. Magically, these all comprise various layers of Goan identity,” said Bambawale.

According to Bambawale and Nayak, their books are attempts to introduce to the masses the side of Goa that the local people often do not want to acknowledge, to offer a holistic understanding of Goa devoid of the rose-coloured lenses that colour most representations.