Panaji, November 2023 – A children’s pavilion built with eco-friendly, reclaimed material, a bioscope offering a glimpse of Goa’s treasure trove, the khazans, an augmented reality project harking back to the past and an installation showcasing the town’s soundscape are four projects that will soon be showcased in Panaji, as part of a public arts project put into action by the Serendipity Arts Grant.

The Serendipity Arts Foundation, the organiser of South Asia’s largest annual multi-disciplinary arts festival in Panaji, has chosen the four unique projects by Goa-based artists, as part of its public art grant, The Island That Never Gets Flooded. The Grant offers a platform as well as a Rs. 3 lakh grant each for Goa-based artists to channel their creative energy into the urban landscape of Panaji. This is the second edition of the grant.

The project aims at suffusing art into the heart of the state capital to foster site-specific artistic initiatives that transform the way one perceives urban environments and contributes a creative dimension to the city’s structural landscape.

“An essential aspect in artist selection is feasibility. For these four artists, we evaluated how their works would fit into a public space structurally and how they would engage with and inspire people, creating lasting memories,” said Veerangana Solanki, visual arts curator for the 6th edition of Serendipity Arts Festival.

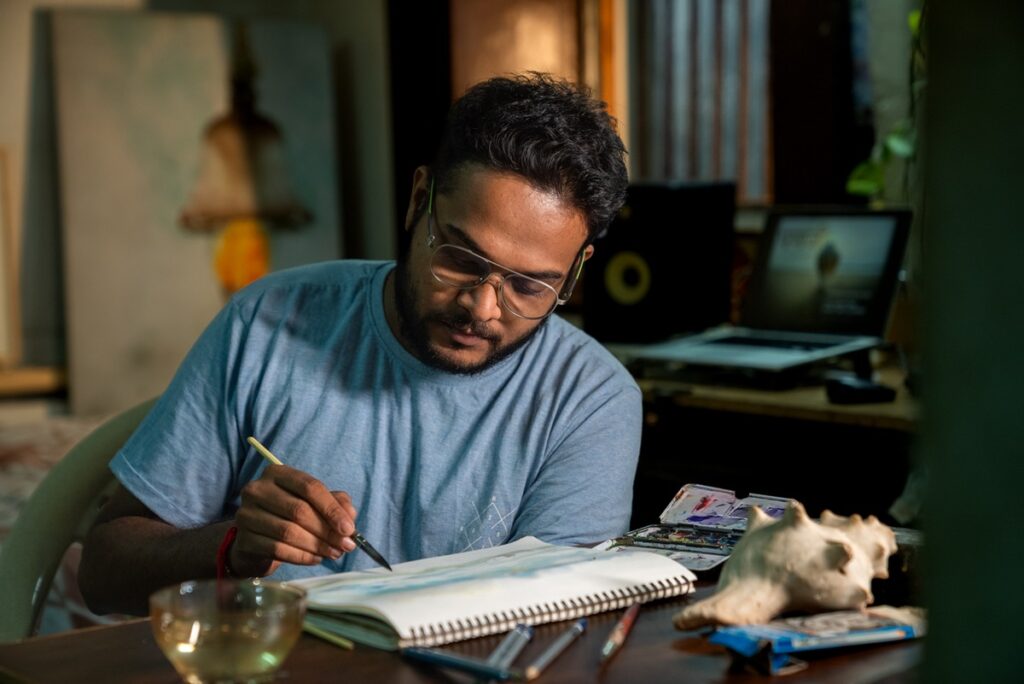

Out of 31 applicants, the four Goa-based artists selected for the project are Ruturaj Parikh, Pakhi Sen, Kalpit Gaonkar and Divesh Gadekar.

Ruturaj Parikh’s ‘Children’s Pavilion’ in Panaji’s botanical park (Art Park) is an interactive space made from reclaimed materials, promoting eco-friendly resources for engaging children. “While our cities are generally riddled with large, imposing infrastructural projects, small and effective public space can change the way people meet, interact and celebrate. This pavilion aims to foreground the impact of such spontaneous spaces,” Parikh said, who is a resident of Panaji and a former director of the Charles Correa Foundation.

Pakhi Sen from Corjuem, an illustrative storyteller who shuttles between Delhi and Goa, crafts an immersive ‘bioscope’ installation spotlighting Goa’s khazan lands. It celebrates community bund networks, preventing floods, sustaining biodiversity, and irrigating fields.

“My understanding of public art harks back to whimsical, playful experiences from childhood, before I knew what it meant in contemporary art. Growing up, bioscopes in public spaces within cities were always a magical gateway into a different realm. The Khazans are an integral part of the Goan landscape and it felt like an opportunity to present a glimpse into the ecology of the interiors of the state,” Sen said.

Kalpit Gaonkar, from Netravali is a local storyteller blending myths and tribal themes, has conceived an augmented reality installation that revives ‘Kasmakaden’, a heritage site in Canacona, symbolising past-present connections and uniting villagers. ‘Kasma’ refers to a particular tree variety beneath which a stone seating arrangement was created for people to assemble, discuss and take important social decisions. The suffix of the installation title, ‘kaden’, means near.

“By showcasing this installation in Panaji, I not only (wish to) honour the city’s rich heritage but also invite reflection on how history’s course has shifted, reminding us of the importance of safeguarding the essence of a place and the power of its people’s collective voice,” says Gaonkar, whose work involves putting together histories and local myths, investigating the relationship between an imagined past and the evolving present in tribal contexts.

Divesh Gadekar, a folk-inspired artist, will create ‘Panaji in My Ears’: a unique sound installation merging conchology, acoustics, and Panaji’s soundscape. Utilising shells, pipes, and vessels at three locations, it amplifies the city’s ambient sounds.

“My father played a large conch at the temple, and I, a curious child, sat beside him with my smaller conch. This humble shell became my first musical instrument, connecting me not just to my father but also to the captivating town of Panaji, Goa. My fascination with sound ultimately led me to conchology,” says Siolim-based Gadekar, who is a percussionist who archives rural Goan musical instruments.